Most lawyers, particularly those practising in the area of construction law, will know that the courts have long held that a builder owes a duty to current and future owners to exercise reasonable skill and care when carrying out building work. But what is the precise scope of a builders’ duty of care?

In modern arbitration and litigation, cases are often won or lost on the strength of the expert evidence. In this article I examine the lessons lawyers and experts can learn from the UK Technology and Construction Court judgment in Van Oord v Allseas.

The Construction Contracts Act 2002 has now been in force for almost 17 years. One of its key features is a process for the determination of construction disputes, called adjudication. Adjudication is designed to be a fast and effective way of determining construction disputes. It has become the process of choice for determining construction disputes which cannot be resolved by negotiation. Yet, many construction professionals (to their credit) have still not been involved in a full adjudication process.

There is a lot of information available about adjudication, including entire text books devoted to the subject. The purpose of this article is to outline the adjudication process in 12 steps (a 12 step programme for construction disputes, if you will):

First, a disclaimer. I'm no tech guru. Far from it. However, I am very interested in the way in which technology is influencing the delivery of professional services, particularly in the legal industry.

I have gone through the process of moving my litigation and arbitration practice to a paperless model this year (not soon enough many would say), and it has revolutionised the way I practise law.

Here are my 5 top tips for those considering going paperless:

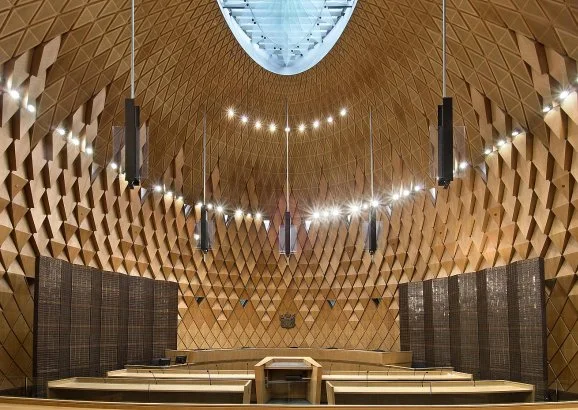

The photo accompanying this post is of the award-winning interior of the New Zealand Supreme Court. If it looks expensive, that's because it was. It was officially opened in January 2010, and built at a cost of $80.7 million. If you are a party to a case in the Supreme Court, that's expensive too.

One of the differences between barristers and solicitors touched upon in my last article was that, as a general rule, barristers have to receive their instructions from a solicitor, often referred to as the "instructing solicitor". That rule has long been known as the intervention rule.

On the 1st of July 2015 changes to the intervention rule came into effect which enable barristers to apply to the New Zealand Law Society for approval to accept instructions directly from clients in certain specified types of cases.

I think so.

After almost 10 years as a barrister at the independent bar, and the last 7 years as a member of Lorne Street Chambers, I relocated my practice to my own chambers at Level 31, Vero Centre, 48 Shortland Street, Auckland on the 1st of December.

My new chambers are in the heart of Auckland's legal and financial district, and close to many of the firms and clients that I work regularly with. They also afford spectacular views over the harbour, from Waiheke to the Waitakere Ranges!

So if you are in Shortland Street, please feel free to call and say hello.